Building a compiler

Sergey, 15 July 2018

This article is devoted to development of a calculating system, which solves a problem of searching an area of curvilinear triangle.

Table of Contents

Task description

The task, I was supposed to solve, was the following: three functions are given, and area of curvilinear triangle between the curves, described by these functions, should be calculated. Also two numbers are given. It’s guaranteed that every pair of curves contains exactly one common point in this segment. Also, it’s guaranteed that these functions are twice differentiable. Functions, that describe triangle, are written in file, using the following format:

The first line of the file contains bounds of the segment, in which vertices of triangle are situated.

Next three lines contain formulas for functions, which are sides of triangle, in reverse polish notation. Every line consists of terms, separated by spaces. The term is:

- A variable, which is denoted by symbol ‘x’.

- A number, which is described in format, supported by scanf function from C standard library. Additionally, constants, described by symbols ‘e’ and ‘pi’, should be supported.

- Unary operation, which can be one of these: sine, denoted by ‘sin’, cosine(‘cos’), tangent(‘tan’) and cotangent(‘ctg’).

- Binary operation, which can be one of the following: addition, denoted by ‘+’, subtraction(‘-‘), multiplication(‘*’), and division(‘/’).

There must be two programs, written in C: a solver, which calculates an area of triangle, using prepared code for calculating the functions, and a compiler, which generates from input file an assembly code, which calculates the function value in given point x, using an x87 instruction set. Building of the program should be performed, using make. Input file should be specified as environment variable during the compilation:

SPEC_FILE=input.txt make

The result must be calculated with an accuracy of 0.1%.

Design

Project structure

Firstly, we need to describe the structure of the project files, which is used. The project directory tree can be described as follows:

CompilerLab

├── build

│ ├── compiler

│ └── solver

├── compiler

│ ├── include

│ ├── src

├── out

└── solver

├── include

└── src

Since compiler and solver are independent programs, each has its own directory tree and its own Makefile, which will be described in detail in the next section. Directory build is used for storing intermediate compilation results. Directory out contains resulting files, such as assembly listing, compiler and solver binaries.

Build system

As project structure is defined, it’s time to talk about program building process. It goes through several stages:

- The compiler should be built.

- The compiler should generate from the input file the assembly listing which is compiled to an object file.

- The solver should be built from sources using the module built in step 2. This step can be made independent from first two steps using dynamic linking.

Let’s look at Makefile, which lets us to perform these tasks:

SPEC_FILE ?= input.txt

YASMFLAGS = -g dwarf2 -DUNIX -felf64

BUILD_DIR = build

OUTPUT_DIR = out

GENERATED_ASM = output.asm

all: build

build: dir solver

run: build

$(OUTPUT_DIR)/main

dir:

mkdir -p $(OUTPUT_DIR)

mkdir -p $(BUILD_DIR)

clean:

rm -r $(OUTPUT_DIR)

rm -r $(BUILD_DIR)

functions.o: $(COMPILER) $(SPEC_FILE)

$(OUTPUT_DIR)/compiler $(SPEC_FILE) $(OUTPUT_DIR)/$(GENERATED_ASM)

yasm $(YASMFLAGS) $(OUTPUT_DIR)/$(GENERATED_ASM) -o $(BUILD_DIR)/functions.o

solver: functions.o

make -C solver

mv solver/solver $(OUTPUT_DIR)/main

compiler:

make -C compiler

mv compiler/compiler $(OUTPUT_DIR)/compiler

.PHONY: solver compiler all clean

As we can see, this Makefile describes building a compiler, building a function module and, finally, building a solver.

Also we would need two Makefiles for building compiler and solver:

compiler/Makefile:

CFLAGS = -g -Iinclude -c -std=gnu99

LDFLAGS = -lm

SRC_DIR = src

BUILD_DIR = ../build/compiler

SRC = $(wildcard $(SRC_DIR)/*.c)

OBJ = $(patsubst $(SRC_DIR)/%.c,$(BUILD_DIR)/%.o,$(SRC))

EXE = compiler

all: dir $(EXE)

$(EXE): $(OBJ)

$(CC) $^ -o $@ $(LDFLAGS)

dir:

mkdir -p $(BUILD_DIR)

$(OBJ): $(BUILD_DIR)/%.o: $(SRC_DIR)/%.c

$(CC) $(CFLAGS) $< -o $@

and solver/Makefile:

CFLAGS = -g -Iinclude -c -std=gnu99

LDFLAGS =

SRC_DIR = src

BUILD_DIR = ../build/solver

SRC = $(wildcard $(SRC_DIR)/*.c)

OBJ = $(patsubst $(SRC_DIR)/%.c,$(BUILD_DIR)/%.o,$(SRC))

EXE = solver

all: dir $(EXE)

$(EXE): $(OBJ) $(BUILD_DIR)/../functions.o

$(CC) $^ -o $@ $(LDFLAGS)

dir:

mkdir -p $(BUILD_DIR)

testdir:

mkdir -p $(TESTS_BUILD_DIR)

$(OBJ): $(BUILD_DIR)/%.o: $(SRC_DIR)/%.c

$(CC) $(CFLAGS) $< -o $@

Solver design

This and the following section describe the structure of our programs and basic interface of our modules.

Let’s begin with solver, because it’s a simplest part of the task. What should it do? This program has previously prepared bounds and functions, so the simplest interface of working with this program is calling it without arguments and getting the result of its work, i.e an area of curvilinear triangle, as its output.

Searching the area of curvilinear triangle consists of two parts: searching the vertices and searching area of triangle as algebraic sum of areas bounded by graphs of functions, the X-axis and vertical lines, passing through found points. Mathematical side of this task is described in detail in my report. So, mathematical module must implement two functions: calculating the root of the equation and calculating the integral of the function. The natural choice for interface of this module will be a function area with the following signature:

solver/include/maths.h:

double area(double a, double b, (double)(*f1)(double), (double)(*f2)(double), (double)(*f3)(double), double eps);

In fact, the fastest methods of calculating the roots of the equation require us to be able to calculate the first derivative. It means that we will have eight arguments, which isn’t very well. To improve our signature, we use two ideas:

- We can use typedef to denote type of the function.

- We can pass functions as array.

Taking these ideas into account, we acquire the following code:

solver/include/maths.h:

typedef double (*function)(double)

double area(double a, double b, function funcs[3], function derivatives[3], double eps);

Compiler design

The second program we need to create is significantly more complex, but the scenario of its use is very simple: it’s given two arguments - name of the file with bounds and functions and name of the file, where the listing should be written. Compiler reads data from the first file and writes the output into the second.

To describe the structure of the program, we need to remember the steps of the compilation process:

- Lexical analysis, i.e splitting input into tokens - some strings, which have some special value in the language.

- Syntax analysis or parsing - building from the sequence of tokens a special structure, called abstract syntax tree, according to the special set of rules, called grammar.

- Semantic analysis - collecting some semantic information from code, for example, types of the variables.

- Generation of code in some intermediate representation, for example three-address code. It allows us to make first three stages independent of the next ones, so we can use different parsers with the same code generation, or, vice versa, use several code generators for one language.

- Optimizing the resulting code.

- Finally, generating the machine (or assembly) code from intermediate representation.

In our case, this scheme can be considerably simplified:

- Lexical and syntax analysis can be united in one stage, because the only tokens are whitespaces and terms.

- Semantic analysis is not needed, except for calculating of derivative (don’t know if it actually can be classified as semantic analysis).

- Optimizations are mostly very simple and can be applied directly to parsing trees, so generation of the intermediate representation becomes obsolete.

Summarizing these ideas, we can come to the following set of modules and their interfaces:

- parser module, which provides the function, transforming a line of text into function, represented by this line.

- derivative module, which provides the function, transforming tree of the function to the tree of its derivative.

- optimizer module, which provides the function, reducing the count of operations in the tree.

- codegen module, which provides function, transforming trees with borders into assembly listing.

Interface of these modules can be represented as follows:

compiler/include/parser.h:

AST* parse(char* line);

compiler/include/derivative.h:

AST* derivative(AST* tree);

compiler/include/optimizer.h:

void optimize(AST* tree);

compiler/include/codegen.h:

#include <stdio.h>

void gen_listing(double a, double b, AST* functions[3], AST* derivatives[3], FILE* out);

Note, that we didn’t state, what the type AST means. There are several ways to implement this structure, we’ll discuss it later. As for now, we’ll just include in every file, which requires this definition, file ast.h. We’ll assume for now, that this file contains a description of type of the parsing tree.

Implementation

In this article we will follow top-to-bottom development strategy. In the first place we will describe the general program logic, using interfaces, given above.

Solver implementation

At the first iteration of building the solver, we’ll provide a stub implementation of mathematical interface, and write the solver program, using it. The simplest stub implementation of area function is simply returning zero:

solver/src/maths.c:

#include "maths.h"

double area(double a, double b, function funcs[3], function derivatives[3], double eps) {

return 0;

}

The high-level logic of the program is straightforward: we just need to call area function on given functions and return the result. The code will be like following:

solver/src/main.c:

#include "maths.h"

#include <stdio.h>

#define ACCURACY = 0.0001,

extern double a, b;

double f1(double);

double f2(double);

double f3(double);

double df1(double);

double df2(double);

double df3(double);

function funcs[3] = {&f1, &f2, &f3};

function derivs[3] = {&df1, &df2, &df3};

int main(int argc, char** argv) {

printf("%lf\n", a, b, funcs, derivs, ACCURACY);

return 0;

}

Note, that we didn’t denote functions with extern keyword, because functions in C are global by default.

If we try to build our project with make now, we will fail, because we don’t have any source code for compiler. So, let’s provide some stub implementation for the compiler:

compiler/src/main.c:

#include <stdio.h>

int main(int argc, char** argv) {

if(argc >= 3) {

FILE* outfile = fopen(argv[2], "wt");

fputs("BITS 64\n \

default rel\n \

global a\n \

global b\n \

global f1\n \

global f2\n \

global f3\n \

global df1\n \

global df2\n \

global df3\n \

\n \

section .rodata\n \

a dq 0.1\n \

b dq 4.0\n \

const1 dq 2.0\n \

const2 dq 4.0\n \

const3 dq 0.2\n \

const4 dq -0.25\n \

\n \

section .text\n \

f1:\n \

push rbp\n \

mov rbp, rsp\n \

movsd qword[rsp - 8], xmm0\n \

fld qword[const1]\n \

fld qword[rsp - 8]\n \

fld qword[const2]\n \

fdivp\n \

fptan\n \

fxch\n \

fstp st1\n \

fsubp\n \

fstp qword[rsp - 8]\n \

movsd xmm0, qword[rsp - 8]\n \

pop rbp\n \

ret\n \

\n \

f2:\n \

push rbp\n \

mov rbp, rsp\n \

movsd qword[rsp - 8], xmm0\n \

fld qword[rsp - 8]\n \

fstp qword[rsp - 8]\n \

movsd xmm0, qword[rsp - 8]\n \

pop rbp\n \

ret\n \

\n \

f3:\n \

push rbp\n \

mov rbp, rsp\n \

movsd qword[rsp - 8], xmm0\n \

fld qword[const3]\n \

fldpi\n \

fmulp\n \

fstp qword[rsp - 8]\n \

movsd xmm0, qword[rsp - 8]\n \

pop rbp\n \

ret\n \

\n \

df1:\n \

push rbp\n \

mov rbp, rsp\n \

movsd qword[rsp - 8], xmm0\n \

fld qword[const4]\n \

fld qword[rsp - 8]\n \

fld qword[const2]\n \

fdivp\n \

fcos\n \

fld st0\n \

fmulp\n \

fld1\n \

fdivrp\n \

fmulp\n \

fstp qword[rsp - 8]\n \

movsd xmm0, qword[rsp - 8]\n \

pop rbp\n \

ret\n \

\n \

df2:\n \

push rbp\n \

mov rbp, rsp\n \

movsd qword[rsp - 8], xmm0\n \

fld1\n \

fstp qword[rsp - 8]\n \

movsd xmm0, qword[rsp - 8]\n \

pop rbp\n \

ret\n \

\n \

df3:\n \

push rbp\n \

mov rbp, rsp\n \

movsd qword[rsp - 8], xmm0\n \

fldz\n \

fstp qword[rsp - 8]\n \

movsd xmm0, qword[rsp - 8]\n \

pop rbp\n \

ret\n", outfile);

fclose(outfile);

}

return 0;

}

This code generates an assembly listing, which contains three functions:

\(f_1(x) = 2 - tg(\frac{x}{4})\)

\(f_2(x) = x\)

\(f_3(x) = 0.2\pi\)

and their derivatives.

If we try to build our program again, it compiles correctly. Running it with

cd out/

./main

gives us:

0.000000

as intended.

Now we need to implement mathematical module. Again, we will write a code, assuming that we already have functions for integrating and searching roots of equation. In this case, we should reach an agreement on which signature this functions would have. I’m going to use the Newton’s method for solving equations and the Simpson’s rule for calculating an integral. According to requirements of these methods, the signatures would be the following:

double integrate(double (*f)(double), double a, double b, double eps) {

return 0;

}

double solve(double (*f)(double), double (*df)(double), double a, double b, double eps) {

return 0;

}

The process of searching area of curvilinear triangle can be divided into three stages:

- Searching the common point of the curves, which are sides of the triangle. Let these points be x1, x2 and x3.

- Searching the area between the graph of the function, X-axis and vertical lines, that passes through found points(i.e integrals of the functions).

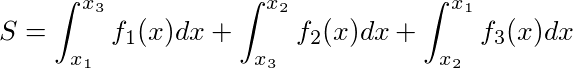

- Searching an area of a triangle, using the formula:

There are two questions, which should be answered, before we’ll be able to implement our area function. Firstly, we should remember, that the Newton’s method can only solve equations of type \(f(x) = 0\), but we need to solve equations of type \(f(x) = g(x)\). Mathematically, this equation is equivalent to the first equation, but in C we have no straightforward way to create the function, that returns \(f(x) - g(x)\), if we have functions, that return \(f(x)\) and \(g(x)\). I chose a little hacky workaround of this problem:

solver/src/maths.c:

//typedef double (*function)(double); - from header file

static function givenf, giveng, givendf, givendg;

inline static double fming(double x) {

return (*givenf)(x) - (*giveng)(x);

}

inline static double dfmindg(double x) {

return (*givendf)(x) - (*givendg)(x);

}

The second question, we should answer to, is which accuracy is acceptable in calculating the integrals and the roots. This question is discussed in detail in my report, so I’ll just provide the code of calculating the area:

solver/src/maths.c:

#include <math.h> // for fabs

double area(double a, double b, function[3] functions, function[3] derivatives, double eps) {

double eps2 = eps/sqrt(3); // accuracy of integrating

double eps1 = eps/10; // this accuracy is defined randomly, it's need for initial values of roots,

givenf = functions[0]; // which can be calculated with better accuracy later, if needed.

givendf = derivatives[0];

giveng = functions[1];

givendg = derivatives[1];

double x1 = solve(&fming, &dfmindg, a, b, eps1);

givenf = functions[1];

givendf = derivatives[1];

giveng = functions[2];

givendg = derivatives[2];

double x2 = solve(&fming, &dfmindg, a, b, eps1);

givenf = functions[2];

givendf = derivatives[2];

giveng = functions[0];

givendg = derivatives[0];

double x3 = solve(&fming, &dfmindg, a, b, eps1);

double neweps1 = eps1 / dist(functions[1](x1) - functions[0](x1),

functions[2](x2) - functions[1](x2),

functions[0](x3) - functions[2](x3)); // New accuracy, roots may need to be recalculated

if(neweps1 < eps1) {

eps1 = neweps1;

givenf = functions[0];

givendf = derivatives[0];

giveng = functions[1];

givendg = derivatives[1];

double x1 = solve(&fming, &dfmindg, a, b, eps1);

givenf = functions[1];

givendf = derivatives[1];

giveng = functions[2];

givendg = derivatives[2];

double x2 = solve(&fming, &dfmindg, a, b, eps1);

givenf = functions[2];

givendf = derivatives[2];

giveng = functions[0];

givendg = derivatives[0];

double x3 = solve(&fming, &dfmindg, a, b, eps1);

}

return fabs(integrate(functions[0], x1, x3, eps2)

+ integrate(functions[1], x3, x2, eps2)

+ integrate(functions[2], x2, x1, eps2));

}

If we run this code, we’ll get again zero as an answer, because we don’t have correct implementations of functions solve and integrate yet. Here they are:

solver/src/maths.c:

double integrate(function f, double a, double b, double eps) {

int n = 1000;

double sum1 = 0, sum2 = 0;

double step = (b - a) / n;

for(int i = 0; i < n; ++i) {

sum2 += ((*f)(a + i * step) + 4*(*f)(a + (i + 0.5) * step) + (*f)(a + (i + 1) * step))*step/6;

}

while(fabs(sum2 - sum1) >= eps) {

sum1 = sum2;

sum2 = 0;

n *= 2;

step = (b - a) / n;

for(int i = 0; i < n; ++i) {

sum2 += ((*f)(a + i * step) + 4*(*f)(a + (i + 0.5) * step) + (*f)(a + (i + 1) * step))*step/6;

}

}

return sum2;

}

static double solve(function f, function df, double a, double b, double eps) {

while((b - a) > (2 * eps)) {

double sign2 = (*df)(a + eps) - (*df)(a);

if((*f)(a) * sign2 < 0)

a = a - ((*f)(a))*(a - b)/((*f)(a) - (*f)(b));

else

a = a - (*f)(a)/((*df)(a));

sign2 = (*df)(b + eps) - (*df)(b);

if((*f)(b) * sign2 < 0)

b = b - ((*f)(b))*(b - a)/((*f)(b) - (*f)(a));

else

b = b - (*f)(b)/((*df)(b));

}

return a + (b - a) / 2;

}

If we run code with these implementations, we should get something like:

1.651666

Which is the correct answer.

Compiler implementation

Since we have finished with mathematical part, let’s proceed with a compiler. As I stated above, we’ll have to implement at least four modules: parser, derivative, optimizer and codegen. But before that we will write a program, assuming that all of these modules have already been written. It should be noted, that before we write all the modules, we won’t be able to build the entire system, so we would build and test a compiler separately. We have a Makefile for it, so we’re able to build it independently from the rest of the program. Since we will work only with the compiler now, I will omit the prefix compiler/ in all file names below.

The high-level logic of the program is:

- Check, whether we have at least two (in fact, three, because the program’s name is the first argument) command-line arguments.

- Get the input and output file names from the arguments.

- From the first line of the input file read bounds of the segment.

- From the remaining lines of the input file read the functions, we need to compile.

- Calculate a derivative for each function.

- Optimize all trees.

- Generate an assembly listing, using bounds and produced trees.

This logic can be expressed with the following code:

src/main.c:

#include "ast.h"

#include "codegen.h"

#include "derivative.h"

#include "error.h"

#include "parser.h"

#include "optimizer.h"

#include <stdio.h>

#include <stdlib.h>

#include <string.h>

int main(int argc, char** argv) {

if(argc != 3) error("You must provide exactly two arguments: name of input file and name of output file.");

FILE *infile = fopen(argv[1], "rt");

char buf[256];

fgets(buf, 256, infile);

double a, b;

if(sscanf(buf, "%lf %lf", &a, &b) < 2) error("You must provide two numbers at the first line.");

AST* functions[3];

AST* derivatives[3];

for(size_t i = 0; i < 3; ++i) {

fgets(buf, 256, infile);

functions[i] = parse(buf);

}

fclose(infile);

for(int i = 0; i < 3; ++i) derivatives[i] = derivative(functions[i]);

for(int i = 0; i < 6; ++i) optimize(functions[i]);

FILE *outfile = fopen(argv[2], "wt");

gen_listing(a, b, functions, derivatives, outfile);

fclose(outfile);

return 0;

}

As you can see, here appeared a module, which we haven’t talked about before, called error. It provides the following, very simple, interface:

include/error.h:

void error(char* message);

It provides a function, handling an error, given as error message. For the purposes of this article, we will choose the simplest way of error handling: the program will just crash and print the error message, so this signature will work well. For the more advanced error handling, it’s good to have a special error type, which can store information about error type and a cause of it. The implementation of this module is straightforward and can be provided at once:

src/error.c:

#include "error.h"

#include <stdio.h>

#include <stdlib.h>

voi.eror(char* message) {

fputs("There was an error during the compilation:", stderr);

fputs(message, stderr);

exit(EXIT_FAILURE);

}

Before we’ll move on, I’d like to draw attention that I won’t handle errors, that are directly related to our compiler project, for example, I/O errors, or allocation errors. In the real world programs these errors, of course, should be handled.

To make the program build and work, we should provide stub implementation for used modules (except already implemented module error), as we did before. Here they are:

src/parser.c:

#include "parser.h"

#include <stddef.h>

AST* parse(char* line) {

return NULL;

}

src/derivative.c:

#include "derivative.h"

#include <stddef.h>

AST* derivative(AST* tree) {

return NULL;

}

src/optimizer.c:

#include "optimizer.h"

void optimize(AST* tree) {

}

src/codegen.c:

#include "codegen.h"

void gen_listing(double a, double b, AST* functions[], AST* derivatives[], FILE* out) {

fprintf(out, "");

}

As we have finished with high-level logic, we can move on to implementation of modules.

AST

As you remember, when we designed a compiler, we left a type of the parsing tree undefined. Now it’s time to fix it and define a type for tree and some interface for it. To do it, we must firstly define, what we will call ‘parsing tree’. In our case, parsing tree will be a tree, which represents an expression in the following manner:

- Every leaf describes an expression of type ‘p’, where p is a constant or a variable ‘x’.

- Every node, which has one child, describes an expression of type ‘expr op’, where expr is another expression, described by the child of this node and op has value ‘sin’, ‘cos’, ‘tan’ or ‘ctg’.

- Every node, which has two children, describes an expression of type ‘expr1 expr2 op’, where expr1 is the expression, described by the left child of given node, expr2 is the expression, described by the right child of given node, and op has value ‘+’, ‘-‘, ‘*’ or ‘/’.

- Parsing tree has no nodes, which have three or more children.

From this definition follows, that we can use two enums:

- the first for describing the type of the node: is it a variable, a constant, or an expression.

- the second for describing of which operator should be applied to operands, if it should. Using these enums, we can describe the type of the parsing tree like this:

include/ast.h:

enum NODE_TYPE {

VARIABLE,

CONSTANT,

EXPRESSION

};

enum OPERATOR_TYPE {

PLUS,

MINUS,

MULTIPLY,

DIVIDE,

SIN,

COS,

TAN,

CTG

};

typedef enum NODE_TYPE NODE_TYPE;

typedef enum OPERATOR_TYPE OPERATOR_TYPE;

struct AST {

NODE_TYPE node_type;

double value;

OPERATOR_TYPE operator_type;

struct AST *first_arg;

struct AST *second_arg;

};

typedef struct AST AST;

Along with the type of the tree, we should define some functions which work with our tree. In the first instance it will be enough for us to have functions for creating and destroying tree and a function to print tree for debugging purposes:

include/ast.h:

#include <stdio.h> // For FILE definition

AST* create_tree();

void destroy_tree(AST* toremove);

void print_tree(AST* tree, FILE* out);

Until we have no implementation of dynamic strings, it’s preferable to print tree directly into the file instead of returning its string representation.

Note, that all the code, put into ast.h, must be placed between lines:

include/ast.h:

#ifndef _AST_H

#define _AST_H

//Our definitions here

#endif

It’s needed, because ast.h included in all header files of the compiler, which, in their turn, are included in main.c, so we can get a duplicate of definitions, so program won’t compile. To prevent this, we define a special macro _AST_H, which marks that this header have been already included.

The implementation of these functions is simple, but lengthy:

src/ast.c:

#include "ast.h"

#include <stdlib.h>

AST* create_tree() {

return malloc(sizeof(AST));

}

void destroy_tree(AST *to_destroy) {

if(to_destroy) {

if(to_destroy->node_type != EXPRESSION) {

free(to_destroy);

}

else {

switch(to_destroy->operator_type) {

case PLUS:

case MINUS:

case MULTIPLY:

case DIVIDE:

destroy_tree(to_destroy->second_arg);

case SIN:

case COS:

case TAN:

case CTG:

destroy_tree(to_destroy->first_arg);

free(to_destroy);

break;

}

}

}

}

void print_tree(AST* to_print, FILE* out) {

char* op;

switch(to_print->node_type) {

case VARIABLE:

fputs("x", out);

break;

case CONSTANT:

fprintf(out, "%lf", to_print->value);

break;

case EXPRESSION:

switch(to_print->operator_type) {

case SIN:

op = "sin";

print_tree(to_print->first_arg, out);

fprintf(out, " %s", op);

break;

case COS:

op = "cos";

print_tree(to_print->first_arg, out);

fprintf(out, " %s", op);

break;

case TAN:

op = "tan";

print_tree(to_print->first_arg, out);

fprintf(out, " %s", op);

break;

case CTG:

op = "ctg";

print_tree(to_print->first_arg, out);

fprintf(out, " %s", op);

break;

case PLUS:

op = "+";

print_tree(to_print->first_arg, out);

fputs(" ", out);

print_tree(to_print->second_arg, out);

fprintf(out, " %s", op);

break;

case MINUS:

op = "-";

print_tree(to_print->first_arg, out);

fputs(" ", out);

print_tree(to_print->second_arg, out);

fprintf(out, " %s", op);

break;

case MULTIPLY:

op = "*";

print_tree(to_print->first_arg, out);

fputs(" ", out);

print_tree(to_print->second_arg, out);

fprintf(out, " %s", op);

break;

case DIVIDE:

op = "/";

print_tree(to_print->first_arg, out);

fputs(" ", out);

print_tree(to_print->second_arg, out);

fprintf(out, " %s", op);

break;

}

break;

}

}

As the form of tree representation I chose a reverse polish notation, because infix notation will require parentheses, which can be difficult to read, especially when the expression is very long. Also, in this snippet I used a feature of switch construction implementation in C: the next case branch will be executed immediately after the previous, if reserved word break isn’t place in the end of it.

Parsing

As I mentioned earlier, parsing is a process of building parsing tree from the input string. There is an algorithm of parsing reverse polish notation:

- Split input line by spaces into terms and create an empty stack.

- Look terms from left to right. Here are three cases for term:

- If the term is a constant or a variable, we just put it onto stack.

- If the term is one of “sin”, “cos”, “tan” or “ctg”, we should take a tree from the top of the stack, and assign it to a child for new tree, which has an expression type, and an operator type, corresponding to the term.

- If the term is one of “+”, “-“, “*” or “/”, we should take two values from the stack and create a tree, which represents an expression of type “expr1 expr2 op”, where op is current term, expr2 is an expression, represented by the top of the stack, and expr1 is an expression, represented by the second value taken from the stack. Resulting tree should also be put onto stack.

- If we couldn’t take arguments from the stack at some stage, the expression was ill-formed.

- If the stack contains more then one element after handling all terms, the expression was ill-formed.

- If the stack i.epty after handling all terms, the expression was empty.

More detailed discussion can be found here.

As we can see, this algorithm requires an implementation of stack. I won’t provide it here, but I will use it, assuming it provides the following interface:

include/stack.h:

#include "ast.h"

typedef struct stack stack;

void clear(stack* st);

void push(stack* st, AST* tree);

AST* pop(stack* st);

int size(stack* st);

stack* create_stack();

void destroy_stack(stack* st);

An example of implementation can be found in my repo.

When we have all necessary tools, we can proceed with an implementation of parsing:

src/parser.c:

AST* parse(char* line) {

stack* st = create_stack();

char* token = strtok(line, " \n");

while(token) {

if(token[0]) {

AST* newtree = create_tree();

if(isalpha(token[0])) {

if((token[0] == 'x') && (token[1] == '\0')) {

newtree->node_type = VARIABLE;

}

else if((token[0] == 'e') && (token[1] == '\0')) {

newtree->node_type = CONSTANT;

newtree->value = M_E;

}

else if(strncmp(token, "pi", 2) == 0) {

newtree->node_type = CONSTANT;

newtree->value = M_PI;

}

else {

newtree->node_type = EXPRESSION;

if(size(st) == 0) error("Ill-formed expression.");

newtree->first_arg = pop(st);

if(strncmp(token, "sin", 3) == 0) {

newtree->operator_type = SIN;

}

else if(strncmp(token, "cos", 3) == 0) {

newtree->operator_type = COS;

}

else if(strncmp(token, "tan", 3) == 0) {

newtree->operator_type = TAN;

}

else if(strncmp(token, "ctg", 3) == 0) {

newtree->operator_type = CTG;

}

}

}

else if(isdigit(token[0])) {

newtree->node_type = CONSTANT;

sscanf(token, "%lf", &(newtree->value));

}

else {

AST *first, *second;

if(size(st) < 2) error("Ill-formed expression.");

second = pop(st);

first = pop(st);

newtree->node_type = EXPRESSION;

newtree->first_arg = first;

newtree->second_arg = second;

switch(token[0]) {

case '+':

newtree->operator_type = PLUS;

break;

case '-':

newtree->operator_type = MINUS;

break;

case '*':

newtree->operator_type = MULTIPLY;

break;

case '/':

newtree->operator_type = DIVIDE;

break;

default:

error("Unknown token.");

break;

}

}

push(st, newtree);

}

}

if(size(st) != 1) error("Ill-formed expression.");

AST* result = pop(st);

destroy_stack(st);

return result;

}

Since we wrote a module, it’s time to test it. In contrast to mathematical module, where we could easily test the work of entire program, testing the entire compiler requires writing at least one additional module, code generator, which is quite complex, so we should think about another way to check the correctness of our program. For example, we can note, that if expr is a valid expression in our terms, then print_tree(parse(expr), out) will write to file out expr, because we chose postfix notation for printing a tree. The only change is that constant ‘e’ and ‘pi’ will be replaced by their numeric values, because we don’t have special type of parsing tree for them. It means, that we can test our program by modifying the main function, adding there some lines in the end of the function just before return:

src/main.c:

print_tree(parse(test1), stdout);

puts("");

char test2[] = "2 x *";

print_tree(parse(test2), stdout);

puts("");

char test3[] = "e sin";

print_tree(parse(test3), stdout);

puts("");

If we build the compiler and run it with command like:

./compiler ../input.txt output.asm

We should see the following output:

2.000000 3.000000 /

2.000000 x /

2.718282 ctg

This approach is simple, but it has many disadvantages. Firstly, all tests are executed in the code of our program, which leads to many problems. For example, error in test causes a crash in a program. Another trouble is that our tests have side effects, which are not defined by the compiler’s interface. Second disadvantage is that we can have only one failing test, and it should be the last, because error in test crashes the program. The first problem can be solved by creating a separate program for testing, but the second requires changing a way of handling errors. However, this problem can also be fixed, if we create an independent program for testing, but this question is currently out of sphere of our interests, so we will defer its discussion.

There is also a feature of our implementation of parser, which causes some problems with testing: the strtok function mutates the string, adding there terminal characters. It doesn’t break our high-level logic, because the source string is used only for parsing, but it prevents us from passing literal strings as parameters to parse function. Passing literals to strtok causes segmentation fault.

When we finish testing, we should remove added lines from the main function to avoid undocumented side effects.

After we have finished a parser module, we can proceed with a derivative module.

Derivative taking

In the previous stage we defined 1-to-1 correspondence between functions and parsing trees. This correspondence allows us finding a tree of function’s derivative by function’s tree, using the following set of rules:

- f’(x) = 0 if f(x) = const.

- f’(x) = 1 if f(x) = x.

- (f(x) + g(x))’ = f’(x) + g’(x)

- (f(x)g(x))’ = f’(x)g(x) + f(x)g’(x)

- (f(x)/g(x))’ = (f’(x)g(x) - f(x)g’(x))/g^2(x)

- (sin(f(x)))’ = cos(f(x)) * f’(x)

- (cos(f(x)))’ = -sin(f(x)) * f’(x)

- (tg(f(x)))’ = -f’(x)/cos^2(f(x))

- (ctg(f(x)))’ = -f’(x)/sin^2(f(x))

Before implementation we should raise a couple of questions. The first is: in some formulas we use f(x) as a node for a tree. Should we copy the tree of f(x) or we can use the same tree? And the second is: which representation should we choose for unary minus operator?

The answer to the first question follows from the logic of destroying tree: we cannot use links to source tree in derivative tree, because if we try to destroy both trees, we’ll get a double free error, trying to destroy source tree twice. It means, that source tree should be copied before calculating a derivative and interface of ast.h should be extended by the following function: include/ast.h:

AST* copy_tree(AST* source);

Implementation of this function is very straightforward: src/ast.c:

AST* copy_tree(AST* source) {

AST *result = create_tree();

result->node_type = source->node_type;

if(source->node_type == CONSTANT) {

result->value = source->value;

}

else if(source->node_type == EXPRESSION) {

result->operator_type = source->operator_type;

result->first_arg = copy_tree(source->first_arg);

switch(source->operator_type) {

case PLUS:

case MINUS:

case MULTIPLY:

case DIVIDE:

result->second_arg = copy_tree(source->second_arg);

break;

}

}

return result;

}

The answer on the second question is in fact a matter of convention, because all the variants we chose can be optimized to one negation command. For clarity, I will translate the negation of expression expr as 0 - expr.

When we have these conventions, we can write the implementation of the derivative function. The full code is very long, so I will provide only the main code and code for taking derivative of operators “+” and “sin”, the rest can be written, using conventions above. The full code can be found here.

src/derivative.c:

AST* derivative(AST* tree) {

AST* result = create_tree();

switch(tree->node_type) {

case CONSTANT:

result->node_type = CONSTANT;

result->value = 0;

break;

case VARIABLE:

result->node_type = CONSTANT;

result->value = 1;

break;

case EXPRESSION:

result->node_type = EXPRESSION;

switch(tree->operator_type) {

case PLUS:

case MINUS:

result->operator_type = tree->operator_type;

result->first_arg = derivative(tree->first_arg);

result->second_arg = derivative(tree->second_arg);

break;

// cases MULTIPLY and DIVIDE

// ...

case SIN:

result->operator_type = MULTIPLY;

AST* leftarg = create_tree();

AST* rightarg = derivative(tree->first_arg);

leftarg->node_type = EXPRESSION;

leftarg->operator_type = COS;

leftarg->first_arg = copy_tree(tree->first_arg);

result->first_arg = leftarg;

result->second_arg = rightarg;

break;

// cases COS, TAN and CTG

// ...

}

break;

}

return result;

}

We can test derivative module by printing a tree, like we did with parser, but since we have a working parser, we can just write expressions for some functions and their derivatives and check that derivative taking is correct. For applying this approach, we should have a following function for comparing trees:

include/ast.h:

#include <stdbool.h>

bool equals(AST* left, AST* right);

There can be several approaches to implementation of these function. For our purposes, the simplest implementation will do:

src/ast.c:

bool equals(AST* left, AST* right) {

double accuracy = 0.000001;

if(left->node_type != right->node_type) {

return false;

}

switch(left->node_type) {

case CONSTANT:

if(fabs(left->value - right->value) >= accuracy) {

return false;

}

break;

case EXPRESSION:

if(left->operator_type != right->operator_type) {

return false;

}

if(!equals(left->first_arg, right->first_arg)) {

return false;

}

switch(left->operator_type) {

case PLUS:

case MINUS:

case MULTIPLY:

case DIVIDE:

if(!equals(left->second_arg, right->second_arg)) {

return false;

}

}

break;

}

return true;

}

Another approach is checking that functions, represented by the trees, are equivalent.

Now let’s describe several test cases:

src/main.c:

void test_derivative() {

char test1[] = "2 x +";

char ans1[] = "0 1 +";

char test2[] = "x sin x cos *";

char ans2[] = "x cos 1 * x cos * x sin 0 x sin 1 * - * +";

char test3[] = "x tan x ctg +";

char ans3[] = "1 x cos x cos * / 0 1 x sin x sin * / - +";

printf("%d %d %d",

equals(derivative(parse(test1)), parse(ans1)),

equals(derivative(parse(test2)), parse(ans2)),

equals(derivative(parse(test3)), parse(ans3)));

}

And add call of this function to main.

If all is correct, the compiler should produce the following output:

1 1 1

The provided approach to testing seems to be very interesting, because it can be easily generalized for any functions, which produce comparable values. Besides that, the testing function can be easily moved to a separate program, so the compiler can be freed from an extra side effects. But this approach does not allow to check side effects of the function. However, in addition to custom error handling, this approach can be a powerful tool for testing a program, so we’ll use it for optimizer too.

It’s also worth mentioning, that function test_derivative has a memory leak. In our model example this does not have a great effect, because trees are not very big, but in a real programs memory leaks should be avoided.

Optimization

As we can see from the last section, derivative taking can produce a very large tree. Translating it may produce very inefficient code, so it would be good to “compress” the tree, removing some unnecessary operations from it. I will show two possible directions of optimization: constant folding and using of mathematical identities.

Constant folding is a way of optimization when each sub-tree, which can be calculated in compile-time, is calculated. For example, tree, described by the expression “x 2 3 + *”, becomes a tree, described by the expression “x 5 *”. Implementation of this optimization can look like this:

src/optimizer.c:

#include <math.h>

void fold_constants(AST* tree) {

if(tree) {

if(tree->node_type == EXPRESSION) {

fold_constants(tree->first_arg);

if(tree->first_arg->node_type == CONSTANT) {

switch(tree->operator_type) {

case SIN:

tree->node_type = CONSTANT;

tree->value = sin(tree->first_arg->value);

destroy_tree(tree->first_arg);

break;

// cases COS, TAN and CTG are omitted, they are similar.

case PLUS:

fold_constants(tree->second_arg);

if(tree->second_arg->node_type == CONSTANT) {

tree->node_type = CONSTANT;

tree->value = tree->first_arg->value + tree->second_arg->value;

}

break;

// cases MINUS, MULTIPLY and DIVIDE are omitted, because they are similar.

}

}

}

}

}

Another area of optimizations is using some mathematical identities. For example, here is an optimizer, which uses identities “x + 0 = x”, “x - 0 = x”, “0 * x = 0” and “0 / x = 0” for simplifying the tree(order is important in this case):

src/optimizer.c:

void mathematic_optimizer(AST* tree) {

double accuracy = 0.000001;

if(tree) {

if(tree->node_type == EXPRESSION) {

mathematic_optimizer(tree->first_arg);

switch(tree->operator_type) {

case PLUS:

mathematic_optimizer(tree->second_arg);

if((tree->second_arg->node_type == CONSTANT) &&

(fabs(tree->second_arg->value) < accuracy)) {

destroy_tree(tree->second_arg);

move_tree(tree->first_arg, tree);

}

break;

case MINUS:

mathematic_optimizer(tree->second_arg);

if((tree->second_arg->node_type == CONSTANT) &&

(fabs(tree->second_arg->value) < accuracy)) {

destroy_tree(tree->second_arg);

move_tree(tree->first_arg, tree);

}

break;

case MULTIPLY:

mathematic_optimizer(tree->second_arg);

if((tree->first_arg->node_type == CONSTANT) &&

(fabs(tree->first_arg->value) < accuracy)) {

destroy_tree(tree->first_arg);

destroy_tree(tree->second_arg);

tree->node_type = CONSTANT;

tree->value = 0;

}

break;

case DIVIDE:

mathematic_optimizer(tree->second_arg);

if((tree->first_arg->node_type == CONSTANT) &&

(fabs(tree->first_arg->value) < accuracy)) {

destroy_tree(tree->first_arg);

destroy_tree(tree->second_arg);

tree->node_type = CONSTANT;

tree->value = 0;

}

break;

}

}

}

}

We see here a new function:

include/ast.h:

void move_tree(AST* source, AST* dest);

It copies tree node from source to dest, destroying source node:

src/ast.c:

void move_tree(AST *source, AST *dest) {

dest->node_type = source->node_type;

switch(source->node_type) {

case CONSTANT:

dest->value = source->value;

break;

case EXPRESSION:

dest->operator_type = source->operator_type;

dest->first_arg = source->first_arg;

switch(source->operator_type) {

case PLUS:

case MINUS:

case MULTIPLY:

case DIVIDE:

dest->second_arg = source->second_arg;

break;

}

break;

}

free(source); // Not destroy_tree! We should move only the node.

}

When we have two optimizers, we can build our optimize function, as a combination of them:

src/optimizer.c:

void optimize(AST* tree) {

mathematic_optimizer(tree);

fold_constants(tree);

}

It’s time to write some tests for our optimizer:

src/main.c:

void test_optimizer() {

AST* tree;

char test1[] = "2 3 * x 7 6 - + *";

char ans1[] = "6 x 7 6 - + *";

char test2[] = "0 x 2 + x cos * /";

char ans2[] = "0";

char test3[] = "2 x * 0 -";

char ans3[] = "2 x *";

tree = parse(test1);

optimize(tree);

printf("%d ", equals(tree, parse(ans1)));

tree = parse(test2);

optimize(tree);

printf("%d ", equals(tree, parse(ans2)));

tree = parse(test3);

optimize(tree);

printf("%d", equals(tree, parse(ans3)));

}

If all is correct, we should get the following output:

1 1 1

The full code of the optimizer can be found here.

Code generation

The last stage of compiling process is code generation. This stage can be considered as the most complex stage of compiling process. In this stage, we should generate an assembly listing, containing the borders from input file, and implementations of functions, that we have as parsing trees.

The assembly listing consists of three parts:

- The part, we call header, containing some YASM directives and info about global labels.

- The .rodata section, containing info about constants, used in code.

- The .text section, containing the implementations of the functions.

It means, that top-level logic can be expressed as follows:

src/codegen.c:

void gen_listing(double a, double b, AST* functions[], AST* derivatives[], FILE* out) {

gen_header(..., out);

gen_rodata(..., out);

gen_text(..., out);

for(int i = 0; i < 3; ++i) {

destroy_tree(functions[i]);

destroy_tree(derivatives[i]);

}

}

The ellipsis there denotes additional arguments, which we don’t know for now.

Let’s talk about each part in detail. The header will have the following form:

[BITS 64]

default rel

global a

global b

global f1

global f2

global f3

global df1

global df2

global df3

The first line tells YASM to produce 64-bit code. The second line tells YASM to produce relocatable code. The rest of lines define, that labels a, b, f1, f2, f3, df1, df2, df3 are global. By default labels are local for file, in which they are declared. Implementation of function, generating header, is trivial, so I will assume, that it is already implemented and has a following signature:

src/codegen.c:

static void gen_header(FILE* out) {

// Implementation

}

Section .rodata contains info about the data, which are not changed during the program execution. We will use this section to store constants, needed for calculations. To collect this info, we could use use just a dynamic array or stack, but this structure will hold some often used constants more than once, what may lead to excess consumption of memory by solver. We can avoid it using a set data structure. The implementation of set goes beyond the scope of this article, so we just assume, that it is already implemented and has the following interface:

include/hashset.h:

#include <stddef.h>

typedef struct hashset hashset;

struct hashset;

hashset* create_hashset();

void destroy_hashset(hashset* table);

void insert(hashset* table, double value);

void append(hashset* table, hashset* toappend);

double* to_array(hashset* table, size_t* size);

Using this structure, we can collect information about constants as follows:

src/codegen.c:

#include "hashset.h"

hashset* collect_info(AST* functions[], AST* derivatives[]) {

hashset* result = create_hashset();

for(int i = 0; i < 3; ++i) {

hashset appended = collect_node(functions[i]);

append(result, appended);

destroy_hashset(appended);

appended = collect_node(derivatives[i])

append(result, appended);

destroy_hashset(appended);

}

return result;

}

Where collect_node function collects constants from a single tree and looks like following:

src/codegen.c:

hashset* collect_node(AST* function) {

hashset *result = create_hashset();

switch(function->node_type) {

case CONSTANT:

insert(result, function->value);

break;

case EXPRESSION:

append(result, collect_node(function->first_arg));

switch(function->operator_type) {

case PLUS:

case MINUS:

case MULTIPLY:

case DIVIDE:

append(result, collect_node(function->second_arg));

break;

}

}

return result;

}

Having these functions, we can generate .rodata section. It has the following syntax:

section .rodata

labelname dq 1.0000

Where labelname stands for the name of the constant, dq means that stored value has size of 64 bits and 1.000 is actually the stored constant. Knowing this, proceed to the implementation:

src/codegen.c:

void gen_rodata(double** constants, size_t *size, double a, double b, AST* functions, AST* derivatives, FILE* out) {

fputs("section .rodata\n", out);

fprintf(out, " a dq %lf\n", a);

fprintf(out, " b dq %lf\n", b);

hashset* table = collect_info(functions, derivatives);

*constants = to_array(table, size);

for(size_t i = 0; i < *size; ++i) {

fprintf(out, " const%d dq %lf\n", i + 1, (*constants)[i]);

}

}

The first two arguments are needed to return from the function array with constants, we’ll need it for functions generation.

To check, that we are in the right way, let’s compile program and see its output:

make

./compiler ../input.txt output.asm

cat output.asm

[BITS 64]

default rel

global a

global b

global f1

global f2

global f3

global df1

global df2

global df3

section .rodata

a dq 0.100000

b dq 4.000000

const1 dq 2.000000

const2 dq 4.000000

const3 dq 0.628319

const4 dq 0.000000

const5 dq 1.000000

Which contain numbers similar to numbers that were in our stub implementation. The only differences are that we have 0 - 1/4 instead of -0.25 and 0.628319 instead of 0.2π. It means, we are ready to go on.

The last and the most complex section is .text section. It contains a code of functions, which would calculate values of given functions in given point x in the following manner:

section .text

f1:

; subprogram for f1

f2:

; subprogram for f2

f3:

; subprogram for f3

df1:

; subprogram for df1

df2:

; subprogram for df2

df3:

; subprogram for df3

Every subprogram will be a sequence of assembly instructions. Every subprogram will have the following line:

movsd qword[rsp - 8], xmm0

This line moves function’s argument to a stack. We will call this line a prologue.

Also, every subprogram will have the following lines in the end:

fstp qword[rsp - 8]

movsd xmm0, qword[rsp - 8]

ret

These lines push value from x87 stack to x86 stack and then move it to the XMM0 register, which should hold return value. The ret command denotes subprogram’s end. We will call these lines an epilogue.

The middle of the function is defined by the tree. We can describe it in this way:

- Tree, representing a constant, is translated to:

fld qword[constx]Where constx is the name, given to constant, which is represented by tree. This command stores a variable constx onto x87 stack.

- Tree, representing a variable, is translated to:

fld qword[rsp - 8]This command stores the value of the argument from x86 stack onto x87 stack.

- Tree, representing an expression of type ‘expr1 op’, where ‘op’ is ‘sin’, ‘cos’, ‘tan’ or ‘ctg’, is translated to code:

... ; code in which expr1 is translated fop ; code of application of operator‘fop’ here is a command or a sequence of commands, which takes value from the top of x87 stack and places the result of application of corresponding onto stack. For example, for ‘sin’ ‘fop’ is ‘fsin’, for ‘cos’ ‘fop’ is ‘fcos’. For ‘tan’ and ‘ctg’ two instructions should be used.

- Tree, representing an expression of type ‘expr1 expr2 op’, where ‘op’ is ‘+’, ‘-‘, ‘*’, ‘/’, is translated in the following way:

... ; code for evaluating expr1 ... ; code for evaluating expr2 fop ; code of application of operator‘fop’ is here a command or a sequence of commands, which take values of its operands from the stack and pushes the result of application of the operator onto stack. For example, if ‘op’ is ‘+’ ‘fop’ is ‘faddp’.

Using all these definitions, we’re ready to write a generator for .text section:

src/codegen.c:

#include <math.h>

#include <stdlib.h>

void gen_prologue(FILE* out) {

fputs(" movsd qword[rsp - 8], xmm0\n", out);

}

void gen_epilogue(FILE* out) {

fputs(" fstp qword[rsp - 8]\n", out);

fputs(" movsd xmm0, qword[rsp - 8]\n", out);

fputs(" ret\n", out);

}

void gen_node(double* constants, size_t size, AST* function, FILE* out) {

size_t j = -1;

switch(function->node_type) {

case CONSTANT:

for(size_t i = 0; i < size; ++i) {

if(fabs(function->value - constants[i]) < ACCURACY) {

j = i;

break;

}

}

fprintf(out, " fld qword[const%d]\n", j + 1);

break;

case VARIABLE:

fputs(" fld qword[rsp - 8]\n", out);

break;

case EXPRESSION:

gen_node(constants, size, function->first_arg, out);

char* fop;

switch(function->operator_type) {

case SIN:

fop = " fsin\n";

break;

case COS:

fop = " fcos\n";

break;

case TAN:

fop = " fptan\n fstp st0\n";

break;

case CTG:

fop = " fptan\n fdivp\n";

break;

case PLUS:

fop = " faddp\n";

gen_node(constants, size, function->second_arg, out);

break;

case MINUS:

fop = " fsubp\n";

gen_node(constants, size, function->second_arg, out);

break;

case MULTIPLY:

fop = " fmulp\n";

gen_node(constants, size, function->second_arg, out);

break;

case DIVIDE:

fop = " fdivp\n";

gen_node(constants, size, function->second_arg, out);

break;

}

fputs(fop, out);

break;

}

}

void gen_function(double* constants, size_t size, char* prefix, size_t number, AST* function, FILE* out) {

fprintf(out, "%s%d:\n", prefix, number);

gen_prologue(out);

gen_node(constants, size, function, out);

gen_epilogue(out);

fputs("\n", out);

}

void gen_text(double* constants, size_t size, AST* functions[], AST* derivatives[], FILE* out) {

fputs("section .text\n", out);

for(size_t i = 0; i < 3; ++i) {

gen_function(constants, size, "f", i + 1, functions[i], out);

gen_function(constants, size, "df", i + 1, derivatives[i], out);

}

free(constants);

}

At this stage compiler produces too much code to check it with a look, it can be simpler to try to build the entire project with make and check that it works. Running the program gives us a familiar result, that we got with the stub compiler:

1.651664

To check, that out program is really correct, it makes sense printing some values of generated functions in some intermediate points.

The full code of program, which we have written, can be found here.

Further improvements

There are many places in our program, which can be improved.

Optimizations

Firstly, we can improve our arithmetic optimizations. For example, we don’t use commutativity and associativity of such operations as ‘+’ and ‘*’. For example, an expression

2 3 x + +

won’t be optimized by our compiler, because it has no constant subtrees. But we can transform it to expression

x 2 3 + +

Which has.

Another example of optimization, which can be performed, is optimization, based on rule x - x = 0, where x can stand for expression or variable.

Another way of optimization is architecture-dependent optimization. We can use possibilities provided by the processor, to create a more optimal code. As example, x87 provides a wide range of commands, which designed for loading constants. Using these commands can reduce memory, consumed by the compiled program.

There is another feature of x87, that can cause some problems. The thing is that x87 stack can hold only eight values. It means, that we should take some actions to avoid its overflow, for example, store values on x86 stack instead of x87, or use SSE instruction set.

Testing

The test system can be significantly improved. As I mentioned earlier, if we create a separate testing program with its own error handling, we will be able to test any function, which uses error handling from error.h. Similarly, we can redefine stdin and stdout, using freopen function to work with functions, that use these streams. There is a methodology of building a program, based on testing, called test-driven development, in which tests are written before the functionality.

Language extensions

We can also extend our language, adding there some operators, or using infix notation. Or we can add an assignment operators and variables, other than x, control operators and other stuff.

Anther direction is porting the compiler to some architectures, different from x86, for example, to ARM.

User interface

Some user interface for compiler and solver can be useful. We can add some command-line flags for compiler and solver, for example “–help”, which would print description of the program and scenarios of its use. Some comments on calculation process can also be useful. They can be added as some debugging flags. It can help in testing of the program.

Refactoring

There are some places in our projects, that can be improved. For example, detaching the logic of walking the tree from the logic of derivative taking, optimizing and code generating, may make code more clear.

Another way of improving our program can be moving building of table with constants to an earlier phase. Then we can use link to this table instead of constant value in the tree, so we can avoid storing the values on the phase of generating .text section, if we find a way to convert this link to a variable name.

Some of these ideas are implemented in my CompilerLab, so check it out.

Resume

In this article we built a calculating system, consisting of the compiler and the solver, which solves a problem of finding of area of curvilinear triangle on the given segment. During writing of this system, we saw some approaches to designing, writing and testing programs and described some was of further improvement of our program.